|

| "Remington Upstrike No. 7" by Joe Carter |

Just as both freedom and discipline are necessary in life, serendipity and design must coexist in a work to make it readable. Fortunately, the world is rich in the interweaving of the two, which can be found almost everywhere, and not least where one lives. Mark Helprin~gaining inspiration from objects in our homes

In his essay, "Bumping into the Characters" in Wednesday's New York Times Mark Helprin reminds us of the value found in the quotidian. He writes about "lovely accidents" which reveal the "purely serendipitous" connections in our worlds, about the accretion of knowledge that builds upon itself, the layers of revelation that can occur when we keep our eyes open, when we are actually present.

The essay is either a memoir in the guise of a how-to essay for writers or vice versa. He talks about something important to memoirists--personal objects laden with storied value. He refers to the serendipity of discovery:

It happens all the time, and where it gets quite interesting is in your own house, because what leaps out at you is so often conjoined with your preferences and your history.Written to describe his process of creating fiction, Helprin also shows the process of crafting memories from random incidents and coincidences. He tells writers to prize their material possessions and actions, to see the worth in everyday objects and insights.

John Ruskin's definition of composition as "the arrangement of unequal things" means much to the memoirist especially. It recognizes the importance of finding connections in the material and immaterial "things" in our lives.

~a collection drives the narrative

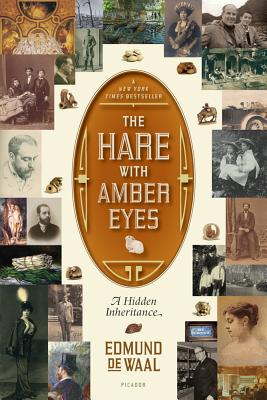

Coincidentally, a book I'm reading now, The Hare with Amber Eyes, traces five generations of the author's family history with a focus on a material object. The writer, Edmund de Waal, references a collection of netsukes, one in particular, as a through-line, or thread, in the narrative. This collection and the author's search for its origin and significance drives the narrative with a meaningful purpose.

~a painting as symbol

In her complex memoir Leap, Terry Tempest Williams traces the significance of one painting, Hieronymus Bosch's "The Garden of Earthly Delights." The painting, a significant leit-motif throughout the narrative, grounds Williams' memories and personal change.

~more about the power of objects

Yesterday's New York Times Style Magazine features Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk whose 2009 book, The Museum of Innocence has spawned an actual museum of the same name to house objects that figure "in a memory Pamuk invented for the characters he imagined." Pamuk got close to his characters by inventing and valuing objects with personal meaning to each.

~ ~ ~

I'm cognizant of the many material things in my home that await memorializing--a lock of my mother's red hair taped inside her silk-covered baby book; my paternal grandmother's wedding veil she carried from old Armenia, crossing the Atlantic in steerage on an Italian steamer and through Ellis Island; an ebony head of Buddha I brought home from Bali, an object that has gazed at me for fifteen years, patiently suggesting that I slow down, put the past in its place and grant the present its due. Things we love to touch, to hold gently and respectfully in our hands, blend their own antique history with ours; our attraction to their power says something about us. Finding out what that is and writing it can memorialize your life experience and give others insight.

Writers unite unequal things with the glue of reflection, thought, insight, conclusions, and fractious memories fragile as shadows. And we "get" epiphanies if we listen closely enough to ourselves. Helprin closes his essay as a model of such composition:

Houses, rooms, our designs of all sorts and all material things will eventually vanish. Because they cannot last, their value is in the present, in memories that die with us, in things that come unbidden to the eye and in the electric, immaterial miraculous spark that occurs when by accident and design they jump the gap and, like life itself, are propagated into something else, becoming for a moment pure spirit, thus to become everlasting.

|

| Helprin in the mid 1950s NY Times photo |

No comments:

Post a Comment